The US Rice Producers Association, representing rice producers in Arkansas, California, Louisiana, Mississippi, Missouri, and Texas, is the only national rice producers’ organization comprised by producers, elected by producers and representing producers in all six rice-producing states.

Since 1997, USRPA has worked hard to…

- Maintain and enhance existing markets, both domestic and international.

- Find and develop new markets for domestic sales and export of rough, brown, and milled rice.

- Give producers a voice in legislative and governmental affairs in Washington D.C.

- Educate and inform producers and the general public about rice and rice market information.

- Expand research activities to develop the rice industry.

Our Story

20 Years and Counting

For the new emerging generation of rice farmers, a look at what happened in the U.S. rice industry 25 years ago will help to answer their questions about why there are two rice groups. Time marches on and the establishment of the US Rice Producers Association 25 years ago came at a time when many of today’s young rice farmers were learning to walk or ride a bicycle. The purpose of this publication is to give those of you who are not aware or have heard an array of versions, the chance to know our early story and why rice farmers are best served by rice farmers. Like any organization created out of controversy and disagreements, the founders of the US Rice Producers Association were rice farmers willing to speak their minds and address the issues openly and honestly. They realized long ago that farmers must take care of their own interests, or someone will take care of it for them. The efforts have not gone unnoticed as evidenced by the new structuring of committees, sub-committees, task forces, state groups, councils, boards, and so forth within the bureaucracy of today’s rice trade organizations. We hope you find this chapter of history interesting, to say the least.

The USA Rice Federation's Original Organization

Washington, DC counsel, Fred Clark (left) and Dennis DeLaughter played instrumental roles in the founding of the US Rice Producers Association in 1997-1998.

As of the early 1990s, three separate groups were representing the rice industry in Washington, DC: the US Rice Millers Association (“RMA”), the US Rice Council (“Council”) and the US Rice Producers Legislative Group (“PG”). Each group had their own focus in the industry. The RMA represented processors, the Council focused on promotion, and the PG concentrated on legislative issues. In 1994, these three groups decided to merge into one larger group in order to increase their collective voice for the coming 1996 Farm bill and the hard fought legislative battle that would precede it. Little did they know that there was also a battle looming in the rice industry itself.

By-laws revealed the lack of trust between millers and producers. When the Original FED was formed, mistrust between the millers and the producers became evident in its formational structure. The Original FED Board of Directors consisted of eighteen board members, six from each of the three sub-groups. The RMA Board Members would be elected by the RMA as a whole. The Council Board Members would be elected by the Council, which could include non-producers. The PG Board Members would be the individual chairmen of the six states’ producer groups, so their six board members came from each state as elected in that state.

The four vote veto power. This board member arrangement was agreed to by all three groups, but only after a provision for veto power was put into the by-laws. In essence, the veto provision said that if any one of the three groups’ board members voted against a motion by four or more votes, the issue was vetoed. So to make it clear, if an issue came up and the vote was 14-4 in favor but the four nay votes all came from one group’s board members, i.e., all from the RMA, then the issue was vetoed and the motion would not pass. It was this veto power that would come into play as the 1996 Freedom to Farm bill was debated and voted on, but it would not be the RMA wielding the veto, it would be the PG.

Penn Owen, a Mississippi rice farmer and founding board member of the USRPA visits with then Mississippi Congressman (and now Senator) Roger Wicker at a USRPA reception in the House Ag Committee hearing room in 1998.

1996 FREEDOM TO FARM BILL

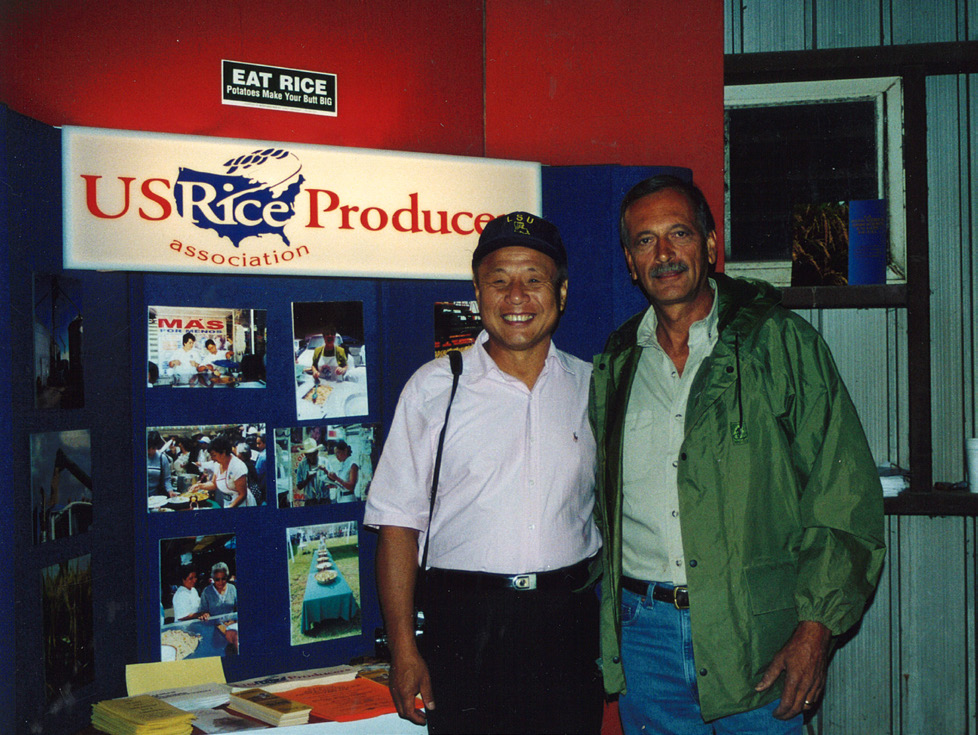

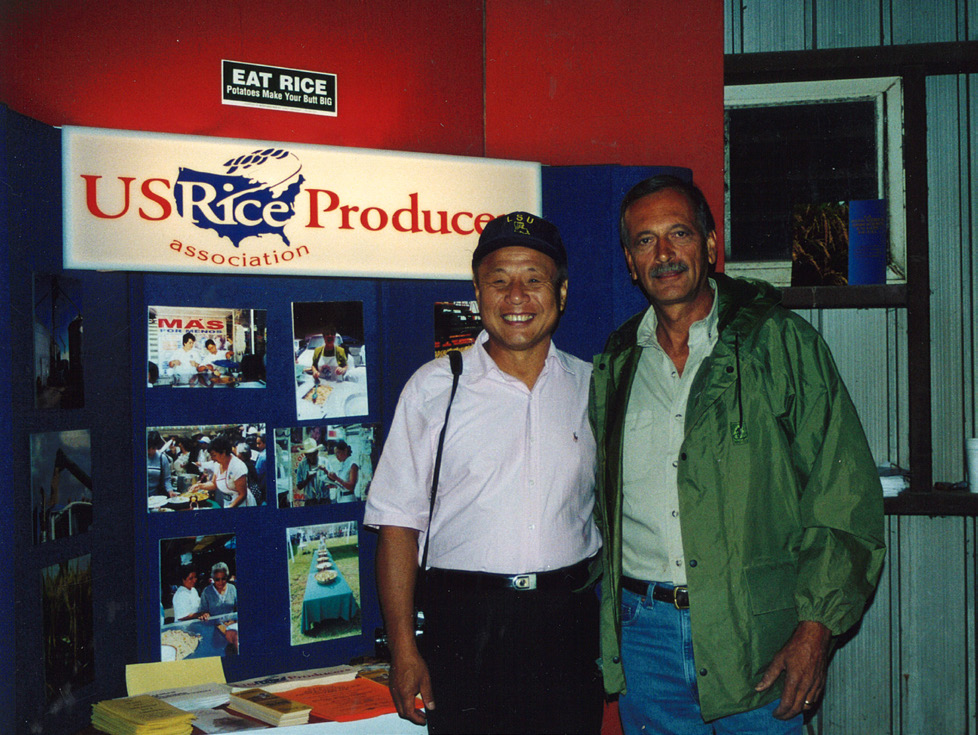

John Alter, a rice farmer from Dewitt, Arkansas operates a booth at the Arkansas Rice Field Day in 2000 on behalf of the USRPA. Alter’s dedicated efforts exposed the need for farmers to be involved in the issues that affect them.

The Original FED dealt with many controversial issues, and in most cases agreements were finally worked out. However, as the 1996 Freedom to Farm bill debate began to heat up, there were some massive changes coming to the farm bill, and those changes would have a gigantic effect on the rice industry, in some cases affecting the producers and millers differently.

WTO restriction hurdles. To understand the reasons for Freedom to Farm, you have to review the farming situation in the early 90’s and how the World Trade Organization (WTO) restrictions at the time motivated changes to the existing farm bill. The farm program in the early 1990’s was based on a planting requirement, and price support was based on a “deficiency payment” that was tied directly to the market price. This type of payment was under attack from the WTO because it was considered to be trade distorting. It became clear that we were going to see ramifications against non-agricultural U.S. interests if payments were tied to markets in this manner. The solution came in the form of the Freedom to Farm bill, which proposed a “direct payment” that was not tied to the market price. However, the key to satisfying WTO requirements was that there could not be a planting requirement. This came to be known as “de-coupling” from the base. This was new because it meant a producer could now be paid without planting the crop for which he was receiving support.

Breaking with a market based farm program. As 1996 rolled on, everyone knew that Freedom to Farm was on its way. This meant that there would be no planting requirement, and a “direct payment” would replace the “deficiency payment,” thereby breaking with a market based program. The RMA and other non-producing members of the rice industry feared that farmers would idle massive amounts of rice ground, which would cut off supplies for the rice infrastructure.

The RMA’s refusal to support Freedom to Farm. As the debate moved into its final phases in the summer of 1996, the RMA presented a motion to the Original FED’s Board of Directors stating that the Original FED did not support Freedom to Farm, and that we, speaking as the entire rice industry, instead supported at least a 50% coupling of planted acres to the base in order to be eligible for any type of payment. In other words, the Original FED wanted ALL CROPS, not just rice, to have a 50% coupling requirement, thereby going against all other major crop lobbies who were by far in favor of decoupling. If the motion proposing the 50% coupling requirement passed, our Washington, DC staff would be instructed to lobby against the Freedom to Farm bill, and we would also be the only commodity to do so.

Dwight Ellis from Walnut Ridge, Arkansas was the first Arkansas rice farmer to raise issues of farmer representation in his state. Ellis worked to form the Arkansas Rice Growers Association that joined the USRPA in 1999-2000. His efforts gained attention and highlighted a need for change.

Although the RMA representatives knew the producers were against the 50% coupling requirement, and the motion wouldn’t pass, they chose to bring it to a vote anyway. After much debate, a vote was called for and the final vote was either 10-8 or 11-7 in favor of the RMA motion. Although the exact vote count is uncertain, we know that four “no” votes came from the PG group—Louisiana, Mississippi, Missouri and Texas all voted not to oppose Freedom to Farm, while the Arkansas and California producers board members voted to oppose the bill. As a result, the motion was defeated because of the veto power clause in the by-laws.

On the other side, when the PG talked about bringing a motion in favor of supporting Freedom to Farm, the RMA let us know they would veto it. The two producer representatives from Arkansas and California also said they would also vote against a new motion in favor, so the vote would be exactly the same, only reversed. The PG decided not to bring the motion to the board because the outcome was known.

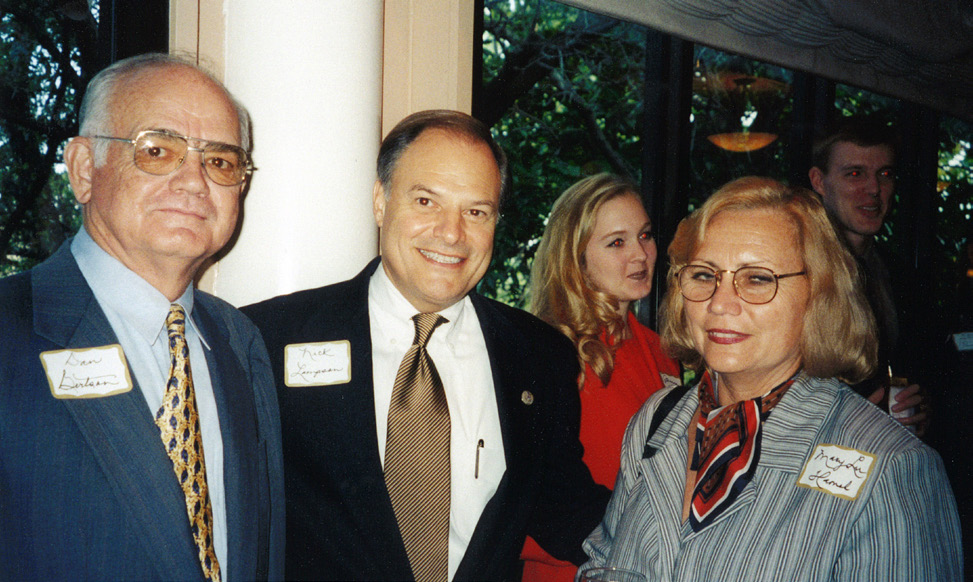

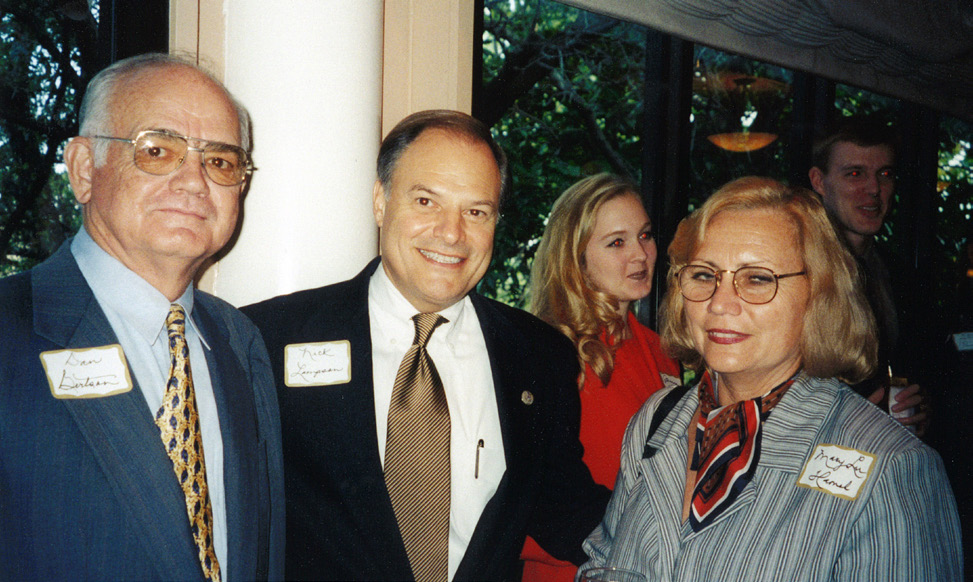

Dan Gertson, a Texas rice farmer and former USRPA board chairman visits with former Congressman Nick Lampson and Maria de la Luz B’Hamel from Cuba’s Ministry of Foreign Trade during the first visit to Texas of a Cuban government trade delegation.

The ability to speak with one voice was lost. The main result of this vote and the board’s lack of unity regarding Freedom to Farm is that the Original FED staff was not allowed to take a position on the proposed farm bill. The staff was told to tell anyone asking for the industry’s position that the industry could not agree and that each sector of the industry would be coming to DC to present their position. In other words, the ability to speak with one voice as an organization was lost, but each individual group could still go to DC and make their case.

Hindsight. It can be argued that had the veto vote not occurred, the farm bill would have passed just as it did. In other words, even had the whole rice industry agreed to fight Freedom to Farm, we would have gotten it all the same, but we likely would have angered the many farming organizations who lobbied hard in favor of Freedom to Farm along the way.

TIME TO CHANGE FED’S ORGANIZATION

With the 1996 Freedom to Farm bill passed, the Original FED’s purpose was now being questioned by many of its members, specifically by the RMA, who believed the organization was upside down when it came to representation. Special board meetings were called, and there was a new focus by those who had lost the farm bill vote to change the rules, particularly to eliminate the four vote veto power.

The RMA challenged the veto vote based on two reasons. First, the majority of the Original FED board had voted in favor of opposing Freedom to Farm. Secondly, Arkansas and California producers representing their farmers had also voted to oppose Freedom to Farm, and they represented by far most rice farmers in the US.

But to the four states that voted in favor of Freedom to Farm, the veto power was critical. Remember, the Original FED would not exist had it not been for the veto that balanced power—that was a crucial condition the three groups agreed on when joining together in 1994. And representatives on the PG for California and Arkansas who had voted against Freedom to Farm both sat on the board of directors of cooperative rice mills in each state and had a history of voting with the mills, creating a clear conflict of interest that was considered detrimental to producers.

Missouri Rice Council Board members from left are BJ Campbell, Larry Riley, Missouri Governor Mel Carnahan (center), Gary Murphy and Sonny Martin at the state capitol during National Rice Month in 1999.

The USRPA board of directors meeting at the Hotel Washington in Washington DC in 1999.

The RMA said they wanted to withdraw from the Original FED unless there was a change in representation within the industry. In an effort to find a compromise, the group hired a facilitator, and the entire board of directors went to Dallas, Texas, for a three-day meeting where they worked to see if there was a way for the three groups to stay together.

Results from the facilitator meeting. The end result of the “facilitator meeting” was a proposal to change the by-laws and the make-up of the board. The RMA would expand from six to nine members on the board. Meanwhile, the Council and PG would be combined, resulting in nine board members from the producer side. These nine producer board members would be heavily weighted toward Arkansas and California. The best analogy is that the proposed new organization would change the board from a U.S. Senate structure where, for example, Texas and Rhode Island have the same number of Senators, to how the U.S. House of Representatives gives Rhode Island two representatives while Texas has thirty-six.

Producers that voted like millers. Some might say there is nothing wrong with the proposed new structure, and in fact, the producers tried to see if we could accept the change by adding one major condition—a stipulation that anyone serving on the board of directors of a mill could not be on the board of directors of the producers group in the New FED. By this time, we knew that many producers in Arkansas were shocked that their representatives had voted against Freedom to Farm when it was clear that by far the majority of Arkansas rice farmers were in favor of the bill. As was pointed out above, the producers on the board who voted against Freedom to Farm looked like producers, talked like producers, and dressed like producers, but they always voted like millers. Under the new proposed structure, many The USRPA board of directors meeting at the Hotel Washington in Washington DC in 1999. producers felt that we were handing the keys of our future to the RMA unless our stipulation was included, but it was completely rejected by the RMA. The vote was now set on accepting the new reorganization plan as drafted at the facilitator meeting, with no additional stipulations.

Mississippi, Missouri and Texas withdraw from the FED and the USRPA was born. Each board member went over the reorganization plan in detail with their state. For example, Texas voted unanimously against the reorganization and also unanimously passed another motion to join a new organization comprised of states withdrawing from the Original FED. When the Original FED Board came back together for the final vote on the reorganization plan, Louisiana was the deciding vote, as its producer representatives voted to accept the change while Mississippi, Missouri and Texas all voted against. Without the four votes to veto the reorganization plan, it passed 12- 6. At that moment, Mississippi, Missouri and Texas withdrew from the Original FED and formed the US Rice Producers Association (“USRPA”). Interestingly, the producer casting the deciding vote for Louisiana to stay in the Federation was named as the new Chairman of the new USA Rice Federation (the “New FED”).

Rice Producers of California board members in 2000 visit Congressman Walley Herger. Left to right are Jerry Cardoso, Manuel Massa, Bert Manuel and Mark Lavy. The RPC called attention to the lack of true farmer representation.

USRPA FORMS AND GOES TO WORK

The USRPA was created under these circumstances in November 1997 and its board of directors consisted of fifteen rice producers, five from each of the three states. Three of those members would come from the Rice Council in each state and two would come from the Legislative Producers Group of each state. The USRPA’s goal was to promote all forms of rice, and it Rice Producers of California board members in 2000 visit Congressman Walley Herger. Left to right are Jerry Cardoso, Manuel Massa, Bert Manuel and Mark Lavy. The RPC called attention to the lack of true farmer representation. set up offices in Houston, Texas. Not long after its formation, the USRPA hired Dwight Roberts as CEO and Fred Clark as Washington, DC counsel. Little did we know that a major issue was about to surface that would put the USRPA on the map in Washington, DC, and onto the forefront of rice producing states’ research efforts.

Rice Producers of California board members in 2000 visit Congressman Walley Herger. Left to right are Jerry Cardoso, Manuel Massa, Bert Manuel and Mark Lavy. The RPC called attention to the lack of true farmer representation.

The TRQ problem. The USRPA made its mark when it discovered that the Tariff Rate Quota (TRQ) problem (happening behind the scenes during all of the reorganization drama in the Original FED) might also be a producer issue, not one that involved just mills. In a nutshell, we discovered that TRQ funds being paid by Europe to the U.S. rice industry actually belonged in part to U.S. rice producers whose checkoff funds had been used to promote that rice in Europe.

The story line from the millers given at the Original FED’s Board of Directors meeting was that all of the funds belonged to mills and they were just trying to come up with a way to divide the funds fairly. Once the USRPA determined that some of those funds should go to producers, we went to Washington, DC, and after a lot of work, we were able to force a solution that let the funds flow to individual state rice research centers. Some will say that more research funds were going to be allocated under the mills’ original plan, but the fact is that all of those dollars would have been allocated through the USA Rice Foundation as stipulated by the RMA. As producers, that was unacceptable to us. To this day, the large amounts of research dollars coming from the different TRQs to individual state research centers is solely because of the USRPA’s actions.

ONE MORE ATTEMPT TO COME TOGETHER

The USRPA grew when independent rice grower organizations in California and Arkansas joined not long after it was formed. It became clear to those in Washington, DC and at the New FED that the USRPA was here to stay. As the next farm bill began to be debated in 2003, there was another attempt to unite the USRPA and just the Producers Group Board that was in the New FED. Again, we met as we had before to see if there was any way to work together apart from the mills. But the same issues that caused the initial split resurfaced, and after several meetings, we determined to stay the course unless the New FED would deal with the conflict of interest issue. Since that time, other than a minor attempt a few years ago, the groups have made no serious attempt to bring about one national producers group.

Original Louisiana Independent Rice Producers Association Board (left to right) are: David Landreneau, Mike Doise, Glenden Marceaux, Phillip Watkins (LIRPA President), Blue Zaunbrecher (LIRPA Vice-President), Chris Krielow (LIRPA Secretary-Treasurer), Mark Heinen, Aaron Lunsford and Jamie Leonards.

ONE MORE ATTEMPT TO COME TOGETHER

After twenty years, there have been some mistakes and victories for both sides. The recent move of Mississippi back into the FED and the victory by the independent Louisiana producers’ group to determine where their checkoff funds go are two examples where both sides had a win, and there are many others we could cite. In fact, we could write a much longer article describing all the good done by the USRPA that wouldn’t have occurred without it. But the purpose of this article is to present the history of how the Original Louisiana Independent Rice Producers Association Board (left to right) are: David Landreneau, Mike Doise, Glenden Marceaux, Phillip Watkins (LIRPA President), Blue Zaunbrecher (LIRPA Vice-President), Chris Krielow (LIRPA Secretary-Treasurer), Mark Heinen, Aaron Lunsford and Jamie Leonards. USRPA came to be, so we will leave with just a few closing thoughts about the positive effects of the USRPA after that split in 1997.

The USRPA’s influence for producers within the FED. First, it’s hard to imagine what the producers’ current involvement in the FED would look like had the USRPA not been formed. The USRPA has had a positive effect for those producers who are currently in a position of influence inside the FED. The way it was headed in 1997, if all states would have bought into the reorganization, true producers would have had little to say regarding direction, especially when it came to the farm bill. Because of the USRPA, the producers’ voice has mattered in the formation of recent farm bills. For example, the husband and wife “active engagement” rule as it is now written has its origin directly attributed to the USRPA and its Washington, DC counsel.

Joe Carrancho, who farms near the Delevan Wildlife Refuge just east of Maxwell, California has never been shy speaking up for rice farmer interests despite the obstacles and roadblocks.

Producers with conflicts of interest within the FED cannot adequately represent producers. Secondly, until producers who have obvious conflicts of interest are recognized as such in the FED, their organization is flawed to the detriment of producers, and as such, the USRPA is truly the only organization representing only the interests of rice producers.

Despite some inherent conflicts, the USRPA does not always disagree with the FED or vice-versa. In fact, on a lot of issues, producers will agree with the millers and other industry participants. But something to consider is this: except for the USA Rice Federation (the FED), in agriculture (to our knowledge), there is no other major crop association in the U.S. where the millers/processors and producers are in one association representing their industry. Some will say the Cotton Council is an example, but in the Cotton Council, only the producer group determines the industry stance on the farm bill. The FED does not include that limitation in their by-laws.

Two associations can speak in unison. Although we respect the men who counseled the group back in 1994 to merge into the Original FED because we needed to “speak with one voice,” the work done by the USRPA to benefit the rice industry and the very fact that other commodity groups have both producer and processor associations that function well together proves that two groups in the same industry can speak in unison.

Promoting rough rice. Finally, there are so many things that have happened over the years in regard to promoting rough rice that would never have happened had it not been for the USRPA. The battles we fought in the early formation of the USRPA with the FED were almost entirely over promoting rough rice exports and the RMA’s bitter fight to slow or stop the flow of rough rice out of the US.

We finish with the adage we began with, “he who fails to learn from history is doomed to repeat it.” The USRPA has been and remains the deterrent for that happening again in the rice industry.

Mississippi's original USRPAboard members from left are Hugh Arant, Nolan Canon, Penn Owen, Travis Satterfield and Rex Morgan along with USRPA staff Dwight Roberts. Picture taken in 1999 at the office of then Mississippi Governor Kirk Fordice.

The US Rice Producers Association, representing rice producers in Arkansas, California, Louisiana, Mississippi, Missouri and Texas, is the only national rice producers’ organization comprised by producers, elected by producers and representing producers in all six rice-producing states.

Since 1997, USRPA has worked hard to…

Maintain and enhance existing markets, both domestic and international.

Find and develop new markets for domestic sales and export of rough, brown and milled rice.

Give producers a voice in legislative and governmental affairs in Washington D.C.

Educate and inform producers and the general public about rice and rice market information.

Expand research activities to develop the rice industry.

To become a member or receive our weekly newsletter, the Rice Advocate, please visit www.usriceproducers.com/membership.

USRPA is an equal opportunity provider and employer

Click Here To Download the Whole Story